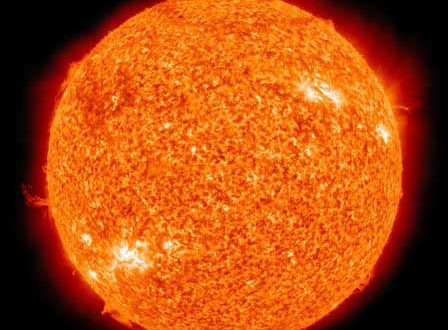

Scientists have captured the deepest radio images of the Sun, an advance that may help reliably predict space weather and its possible effects on Earth.

The Sun is probably the most studied celestial object, but it still hosts mysteries that scientists have been trying to unravel for decades, for example, the origin of coronal mass ejections which can potentially affect the Earth.

A team of scientists at the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics (NCRA) in Pune, Maharashtra have been leading an international group of researchers to understand some of these mysteries.

“The sun is a surprisingly challenging radio source to study. Its emission can change within a second and can be very different, even across nearby frequencies,” said Divya Oberoi, from NCRA, who led the study published in the Astrophysical Journal.

“In addition, the radiation due to the magnetic fields is so weak that it is like looking for the feeble light from a candle in the beam of a powerful headlight,” Oberoi said in a statement.

“On top of this, seeing coronal emission at radio frequencies is a bit like looking through a frosted glass, which distorts and blurs the original image,” he said.

The Sun has some of the most powerful explosions in the solar system. Their possible impacts on Earth include electric blackouts, satellite damage, disruption of GPS based navigation, and other sensitive systems.

Hence, it is becoming increasingly important to understand and predict space weather reliably.

The magnetic fields in the sun’s atmosphere, the corona, are the energy source for these massive explosions, and they are notoriously difficult to measure.

Observations in radio wavelengths are best suited for this problem, but even there, this information is very hard to extract.

A new telescope extremely well suited for solar studies has recently become available: the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) in Australia.

To keep up with the rapid changes in solar emissions, it is necessary to make images of the sun at every half-second interval, and also at hundreds of closely spaced frequencies, totalling to about a million solar images every hour.

The researchers recently developed an automated software pipeline for making these images.

“The solar images from this pipeline also offer the highest contrast, which has ever been achieved, and are a big step toward understanding space weather,” said Surajit Mondal, the lead author the study.

Dainik Nation News Portal

Dainik Nation News Portal